Kenyon’s Quiet Revolution

A casual reader of the Jan. 31, 1947, issue of the Collegian might miss the small sidebar article under “News Briefs,” but the ripples of the impact of the closing sentence can be felt on campus today, more than 70 years later. The short report recaps a visit to campus by “Negro poet” Langston Hughes, who “won the acclaim of an enthusiastic Kenyon audience.” In addition to his formal talk and reading, Mr. Hughes spoke informally in Peirce Lounge, and, as the article concludes, “…one of his most provocative questions was ‘Why aren’t there any Negroes at Kenyon?’”

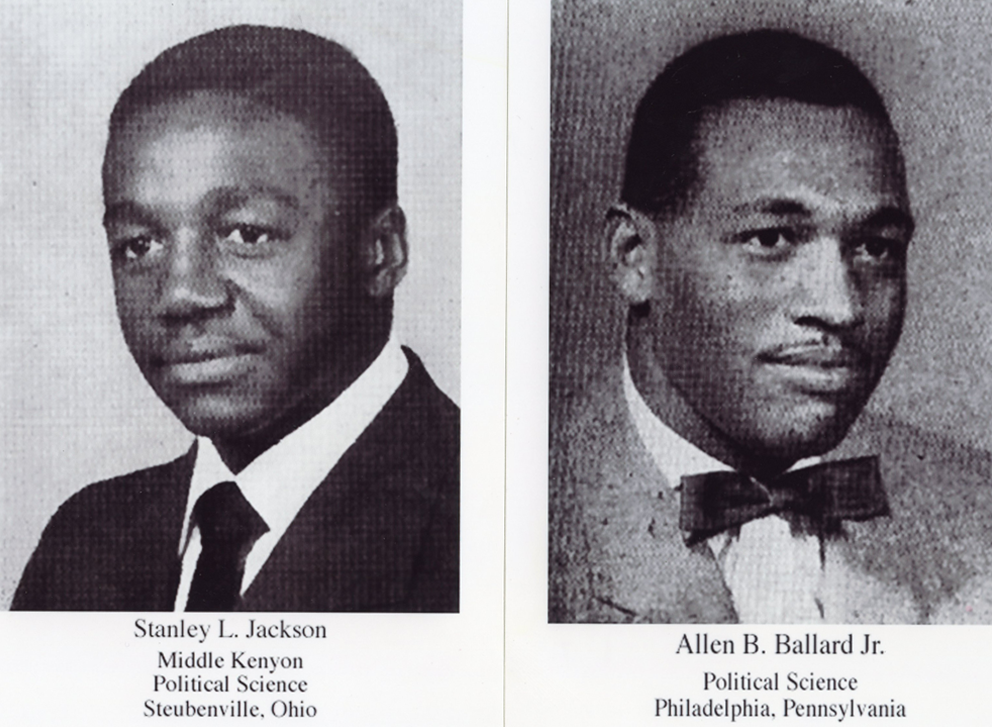

About 18 months later in the fall of 1948, Stanley Jackson ’52 arrived as a first-year student on Kenyon’s campus, one of only two African American students (the other was Allen Ballard ’52) enrolled at what had been an all-white campus. And thus began Kenyon’s slow (at times glacially slow) movement toward a diverse student body.

Mr. Jackson passed away in February. At Kenyon, he excelled on the football field (he was a member of the undefeated Lords squad of 1950) and as a student and community member. Mr. Ballard remembers Mr. Jackson’s inner strength and character on campus, and that “everybody on campus loved him.” Mr. Jackson was a loyal Lord and deeply connected to Kenyon throughout his life after the Hill. At his funeral, he was laid to rest wearing his Kenyon tie. Personally, I am deeply appreciative and indebted to the critical role that Mr. Jackson and Mr. Ballard played in blazing the trail for so many students, faculty and staff of color to become a part of the Kenyon family.

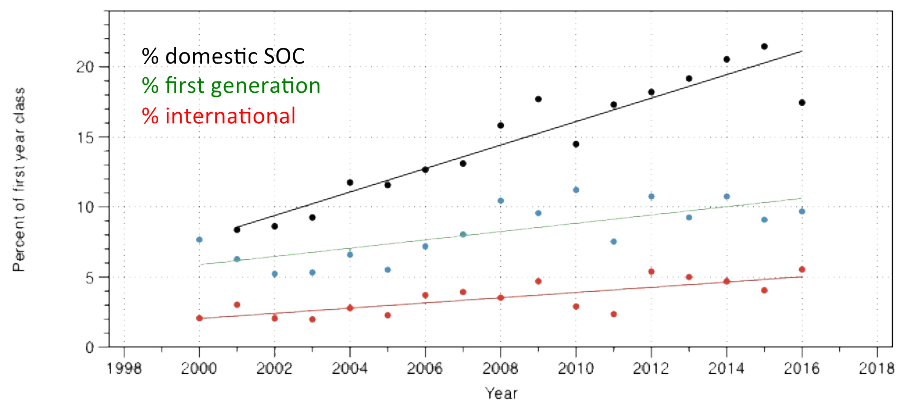

The numbers of students of color on campus remained in the single digits until the late 1960s; and, until the year 2000, the percentage of the student body identifying as students of color on campus (including African American, Latinx, Asian American and Native American students) was at about 8 percent. The percentage of students who were international in the year 2000 was about 2 percent. In the 17 years since then, both of those figures have more than doubled (through all four classes, Kenyon today is 20 percent students of color and 5 percent international). Other markers of diversity have been on the rise as well. In 2000, only about 6 percent of our students were the first in their families to attend college, whereas now about 10 percent of Kenyon students are first generation. And though Kenyon was late compared to its peers to embrace racial diversity, it has been catching up quickly: While our neighbor Oberlin College admitted its first African American students in 1835, 113 years before Kenyon, the numbers of students of color on our two campuses are comparable today.

I have heard many alumni comment on how much the physical campus has changed in the past 20 years, with new buildings (the science quad, the renovation and expansions of Peirce and Rosse, the KAC, Gund Gallery, etc.) serving as reference points of both pride and angst about change at Kenyon. Similar tones are heard even here on campus, where the pages of the Collegian regularly feature pieces lamenting physical changes to campus.

Yet the most substantial changes to Kenyon in the past 20 years are not to the physical campus but rather to the demographics of the students and faculty. This graph says it best:

The data are clear — Kenyon’s diversity trajectory has been steadily upward since 2000. This is simultaneously revolutionary and evolutionary: The faces of the campus have changed dramatically (especially if one were to compare a profile of Kenyon in, say, 1985 to the Kenyon of today). Throughout this evolution, Kenyon has remained committed to its core mission of providing an excellent liberal arts education and its core values of community.

Moreover, our institution is stronger academically and richer culturally because of these changes. Research has illustrated the importance of diversity to one’s learning environment; as a 2015 New York Times article recapped, “By disrupting conformity, racial and ethnic diversity prompts people to scrutinize facts, think more deeply and develop their own opinions. … [S]uch diversity actually benefits everyone, minorities and majority alike.” College graduates in the year 2017 need to have competence at engaging across cultural boundaries, and a diverse campus is an important place to hone these critical skills. And increased diversity is mandatory for any institution committed to excellence; with children of color under the age of 18 scheduled to become the majority of all U.S. children by 2019, Kenyon must continue to improve its demographic profile in order to continue its role in graduating the next generation of great writers, scientists, artists, entrepreneurs and civic leaders.

An all-too-common narrative about contemporary higher education is that colleges and universities have become “bubbles” of homogeneous, fragile students. This is often placed in a vague historical context, that somehow this is a “new” development, a fall from grace from the unidentified glory years when campuses were more diverse and the students more hardy. This simplified narrative is ahistorical, as illustrated by Kenyon’s story: By any measure, on his historic visit 70 years ago, when his provocative question pierced momentarily the Gambier bubble, Langston Hughes found a more isolated and more homogeneous community than he would encounter today. Indeed the story of Kenyon — and the story of U.S. higher education in general — is one of increasing inclusion of voices and perspectives over time, with students who are more agile and experienced at confronting and navigating difference than before.

Our work in this revolutionary evolution is far from complete. While we can recognize the great strides Kenyon has made in the past two decades, we cannot rest here. Our efforts and commitment to continue this trajectory — to continue to build and support a diverse community — must be redoubled. Increasing our endowment resources for financial aid is the top priority of our developing comprehensive campaign. We are renewing our focus on socioeconomic diversity. In this spirit, we have increased our financial aid budget by more than 10 percent for the coming academic year, and we have joined The American Talent Initiative, a nationwide consortium of leading institutions committed to expanding access and opportunity for low-income students. For the Class of 2021, we are increasing by 50 percent the number of students in our Kenyon Educational Enrichment Program (KEEP), recruiting and supporting first-generation and underrepresented students to Kenyon, including the first KEEP S-STEM cohort, aimed at boosting representation of students in the sciences.

As we move forward, there are new challenges that lay ahead. In addition to continuing the drive to increase racial and socioeconomic diversity at Kenyon, we must recognize that our understanding of diversity must become more textured. We need to be attentive to access on campus for students with a range of physical challenges; to the safety and inclusion of members of the LGBTQ+ community; to how we move beyond our increased engagement with the Mount Vernon and Knox County communities toward the increased recruitment of outstanding Knox County students. Moreover, diversity doesn’t automatically produce inclusion, so our efforts at bringing diverse students to campus must always be coupled with work toward ensuring their place as equals within our community.

This is challenging work, with achievements coming in steady increments, with occasional setbacks that must be overcome. But as I reflect upon the courage, strength, and character of Stanley Jackson ‘52 — a Lord through-and-through, who embodied both revolutionary change and steady evolution at Kenyon — I know that we will succeed in moving Kenyon ever forward.