Lessons from a Molecular Miracle

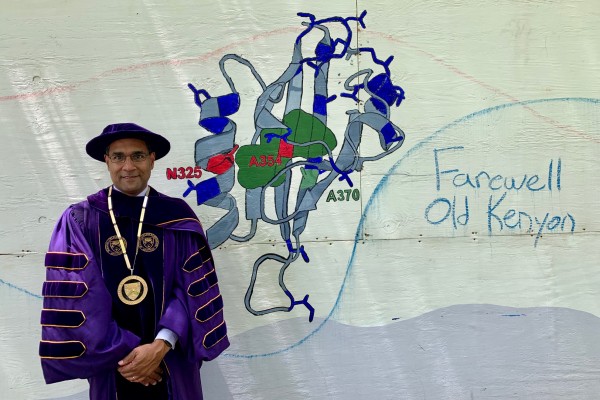

Walking to my office in Ransom Hall one morning in March, I saw an amazing and delightful sight on the construction wall: A group had painted a model of a protein structure in exquisite and beautiful detail. I was out of town the day it was painted, so for me the appearance of a protein structure on the wall, positioned so that I could see it from my office window, felt like some sort of miraculous visage, a mysterious appearance of something so grand and thought-provoking that I could not stop talking about it (as some of you who came to my office or saw me on Middle Path that week experienced firsthand).

I welcomed you to Kenyon four years ago with Convocation comments invoking life lessons from the laws of thermodynamics. So as you prepare to leave this Hill, I hope you can indulge me with one last geek-out session about the lessons on your Kenyon education that one can glean from the molecule that is on display on the construction wall. (I consider this the construction wall miracle of 2019.)

The protein painted is an aryl hydrocarbon receptor from a salamander, described in a 2015 research paper by Kenyon’s own Wade Powell, professor of biology. Yet it is not the specific molecule that gives me joy, but rather its iconography. The structure is drawn in the form that biochemists have come to call a Richardson Diagram, developed by (and named for) Jane Richardson, a major figure in protein biophysics and one of my intellectual heroes. Richardson studied both physics and philosophy as an undergraduate, then went on to graduate study in philosophy in the 1960s. But she found focusing exclusively on contemporary philosophy unsatisfying. She took on a position as a technician in a chemistry lab, where she discovered an interest in the newly emerging field of protein structure determination, in particular the challenge of how to make sense of the growing amount of data emerging on molecular structures.

In order to tackle this problem, Richardson applied the approaches of traditional natural philosophy to the study of molecules, looking for patterns in shapes and structures and classifying the proteins accordingly: a 20th-century adaptation of methodologies dating to Aristotle. In order to make this process more efficient, she developed a visual language for drawing proteins, reducing the complex atomic coordinates into easy-to-read (and aesthetically striking) patterns of colorful ribbons and arrows. Finally, from her interest in art history, she borrowed tools and terminology used to describe ancient Greek and Roman pottery and mosaics to describe proteins, making terms such as “Greek key” mainstays within biochemistry textbooks.

To me, Richardson has always been an exemplar of the power of a liberal education: the ability to look at problems from a different perspective, to borrow and integrate ideas and methodologies from a range of disciplines in order to forge something new and innovative, yet with a keen eye toward the power of art and narrative to convey understanding and insight. The heart of a liberal education is not merely exposure to ideas, concepts and methodologies from the arts, humanities, social and natural sciences, but rather the challenge to integrate ideas across disciplinary boundaries. The pressing social and political problems of our time, whether climate change or economic inequality, all require the rigorous and fearless integration of diverse ideas, approaches and techniques. Richardson’s ribbon diagrams, including the image on the construction wall, are artifacts which remind us of this.

But perhaps the most powerful lessons to be gleaned from Richardson’s work come from her own words. In an interview, she describes her creative and innovative work as driven by an approach of “exhaustively looking, in detail, at each beautifully quirky and illuminating piece of data with a receptive mind and eye. … One can gain fruitful insights through the inherent charm of close acquaintance with the phenomena.”

As Professor Holdener described yesterday in the Baccalaureate address, we are living in an era where some loud voices assert that belief “in your gut” is the equivalent of rigorous analysis. We are living in an era when it is all too easy to have misplaced certainty in one’s own views and close one’s mind and eye to differing perspectives. We are living in an era when engagement at a distance is too often favored over close acquaintance, where hashtag activism too often substitutes for direct work to solve problems, when trolling online replaces direct, honest and respectful communication. We are living in an era where the beautifully quirky is too often undervalued, and the inherent charm of close acquaintance is too often overlooked.

I hope you have found that your Kenyon education has prepared you to oppose each of these trends: to approach difficult problems with thoughtful rigor, to keep your mind open to different ideas and perspectives, to be fearless and engage closely with both phenomena and people, to find joy and charm in observation of the world around you. Our world needs your leadership and example in all of these areas.

Because this is Kenyon, you’ll find it unsurprising if I jump from Richardson’s protein biophysics to the topic of poetry, so I have one more thought to offer you. (Consider this one last close-read of a poem for the road.) In her poem “Ars Poetica #100: I Believe,” Elizabeth Alexander writes,

Poetry is what you find

in the dirt in the corner,

overhear on the bus, God

in the details, the only way

to get from here to there.

Poetry (and now my voice is rising)

is not all love, love, love,

and I’m sorry the dog died.

Poetry (here I hear myself loudest)

is the human voice,

and are we not of interest to each other?

Much as Richardson describes the exhaustive examination of each piece of data as essential to the work of a protein chemist, Alexander describes in similar terms the job of the poet as being attentive to detail, from the dirt in the corner to the conversation on the bus.

But these last two lines introduce something important and new: the reminder of the importance of the human voice, and the importance of taking interest in those around you. Your Kenyon education has not been in isolation; you have lived within a community, in which you have forged relationships with fellow students, faculty and staff — relationships that will last far into the future. We were all brought together here four years ago from different parts of the country and indeed, different parts of the world. We have cared about each other, learned from each other, supported each other through challenging times and shared moments of frustration, but also shared moments of joy and celebration. And I’d argue that it all began with the simple act of taking an interest in each other.

So as you leave this Hill and start your post-Kenyon lives, continue to practice the modes of thinking represented by Richardson’s beautiful diagrams. And, please also keep this in mind: Empathy, support, respect, and indeed all of the things that can make a community function well begin with the simple act provoked by Alexander’s concluding question: Are we not of interest to each other?

I wish you the best, and I am confident that your Kenyon education will serve you, and our world, in the years to come. And, please do keep in touch — I hope to see you back on campus.