Kenyon and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

Kenyon has taught me how to think. Well, actually, in the interest of full disclosure — first, Kenyon humbled me into admitting I didn’t yet know much. I was clever, but in high school I produced more heat than light. Now, I can penetrate, analyze, reason my way through most anything. I have a better feel for others and, most importantly, I pretty well know myself. But I’ve got no grasp on motorcycles.

In the literal sense of the word, motorcycles are awesome; they inspire awe. They have an immediate beauty. It’s cool, but we don’t know why. One with the bike, one with the road, nothing but sky — what a singular pleasure! From motorcycles, I better understand the cavalry of which I read in war literature; from both I get some secondhand sense of riding’s thrill.

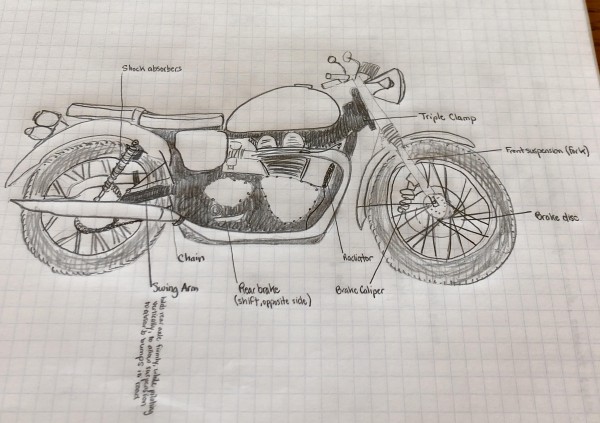

Secondhand, because (as I must admit) I’ve never ridden a motorcycle. Moreover, I’ve got only a vague idea of how they work. So, like a good Kenyon student, a few weeks ago I began to educate myself. I got myself a notebook, sketched a Triumph Bonneville T100 (beautiful, if prohibitively expensive) and labelled its parts, then listed a motorcycle’s functions and component assemblies. I learned that the pistons move up and down inside of a cylinder block, that their movement compresses fuel, which ignites with air and powers the engine. I learned that the horn depends only on the battery, so a check of the former is actually a test of the latter. I got distracted, and began to learn about the history of the internal combustion engine (as I said, I approached this like a Kenyon student).

The intellectual humility I learned in the classroom reflects the simplicity of Kenyon life. Here on the Hill, it’s just us and the trees and the sky. Just as I know there is so much I don’t know, there’s so much that I can’t control. I’ve learned here that happiness depends upon the affirmation of limitations, including our uncertainty about our place in the world, for no matter how much philosophy I read, there’s no definite answer to that question. But a motorcycle makes sense: it’s a closed, knowable system; having learned it, I could fix it, and ride with peace of mind and complete satisfaction.

I should note that my friends don’t quite get why this ranks so highly in my pantheon of interests. Most Kenyon students aren’t teaching themselves about the internal combustion engine. But last year an idea tiptoed into my head, built itself a house and, ever since, resides in my daydreams. So, it’s actually very Quintessentially Kenyon that I should use my skills to realize that dream.

The idea: for this young man to go west. I could ride north from home, Los Angeles; up the coast, through San Francisco to Portland; and across the Rocky Mountains, south through national parks, camping in Zion and Grand Canyon and Joshua Tree. As clickers of the link will see, Bing Maps has told me this trip would take upwards of 45 hours of riding, which I reckon I’d do in about two weeks.

A gander at satellite imagery of the American West confronts the viewer with stark, rugged beauty. Scan over the plains to the East and you’ll see rich valleys, thick forests, great rivers — but I long for tall mountains and red rocks and wooded coastline. I want to get around by getting grease on my hands, to lubricate the chain, and mind the oil. I want to work, to learn the mechanical art. My bike will hum and I’ll smile with it, throw my leg over the saddle, and set off for the horizon.