On Childhood Books, Constructive Criticism and English Papers

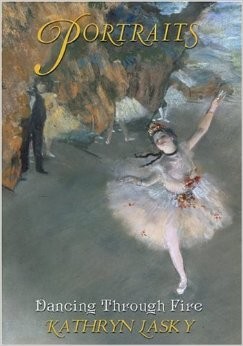

When I was in elementary school, I read this book about an aspiring ballerina. It was one of those books you buy from a Scholastic mail-order book-fair catalog sort of thing — you know the type. I was young and hadn’t yet realized that ballet was not actually my calling, so I was still taking ballet classes four days a week; therefore the beautiful Degas painting of a ballerina on the cover of the book was enticing enough to warrant my begging my mom to order it for me.

I wish I could remember more about this book, like what it was called or who wrote it, but it still lives on my bookshelf at home in California. (Update: A quick Google search has informed me that the book is called Dancing Through Fire by Kathryn Lasky.) It’s about a girl (who the Internet reminds me is named Sylvie) growing up in Paris during the time of the Franco-Prussian War. She lives with her very poor mother in a tiny Parisian apartment and is training full-time to become a prima ballerina, with the hope of being able to support her mother through her dancing.

A specific scene from this book has stuck in my head for many years. It is one in which Sylvie and her friend are talking after a ballet class taught by a particularly prestigious teacher. They’re comparing how many corrections the teacher gave each of the girls in the class, and Sylvie explains to the reader that the more corrections a dancer receives, the better. Being corrected means you are worthy of being noticed, and you have the potential to improve. If the teacher doesn’t think you have promise, he won’t waste his time giving you notes.

This concept made no sense to me when I was younger, when getting an assignment back slathered with multiple corrections felt like and meant that I was doing something wrong. The goal was for my assignments to be graded with nothing but an A at the top and maybe some nice comments at the bottom.

Over the past year and a half at Kenyon, I have been reminded many times of this particular passage in that somewhat forgotten book. When I received my first graded English paper here, I scrolled quickly through the pages and saw comments everywhere. Initially, this led to dismay. Now, it leads to delight.

This shift from dismay to delight was aided in part by this book from my childhood, which helped me realize that comments are not equivalent to failure, but are, in fact, how you learn. Professors’ notes on my papers have taught me to become a better writer and thinker. I now look forward to getting papers returned, with the knowledge that my professors are actually reading, thinking about and engaging with my papers. I appreciate their feedback, which is consistently helpful and thought-provoking. I can only hope that they see the promise in my work that little Sylvie’s ballet teachers saw in her dancing 145 years ago in Paris.