Sharing a Little Piece of My Soul

On Jan. 21, I will give a 10-minute presentation that will somehow encapsulate almost 35 pages of writing, six months of research and infinite passion. Those 10 minutes are a part of the history department’s annual senior research conference. As a sophomore, I attended the conference. I watched seniors share their own research and respond to questions from professors and peers in the audience. I remember I was sitting in the back of the auditorium, thinking to myself, “This is what I’m going to do when I’m a senior.” Throughout my senior year, I’ve been looking forward to this moment.

For every research paper I’ve worked on during my time as a history major, I’ve tried to put a little piece of my soul into it. After all, if you have no love for the story, you won’t commit yourself to telling it in the proper way. History takes a bit of obsession to make it work. You have to be someone who finds value in spending hours sifting through sources. You master the index section of any book. You don’t mind dusty newspapers or staring at computer screens for far longer than is healthy. This presentation is my chance to share that soul and obsession.

Our senior exercise, a 35-page research paper, is supposed to be a culmination of that experience. When I started this process at the beginning of fall semester, I knew that I would choose a topic rooted in the United States. The specific subject, however, was one of those dusty artifacts that history lovers fawn over.

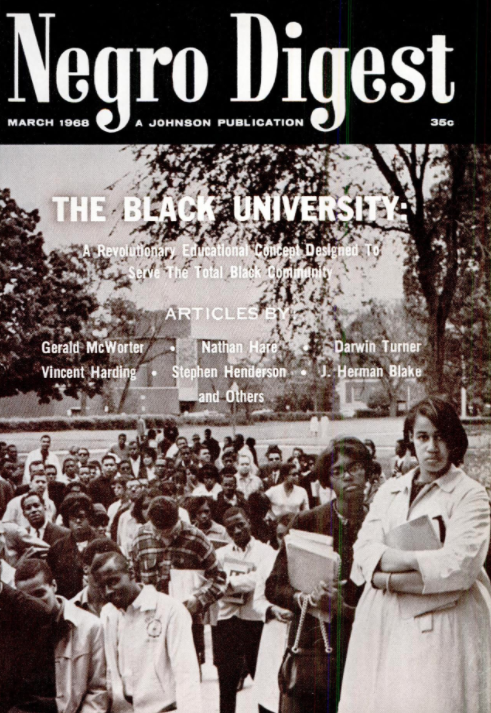

It was an edition of the Negro Digest from 1968. The cover declared: “The Black University: A Revolutionary Concept Designed to Serve the Total Black Community.” The Black University was a concept developed in the Negro Digest over three special editions in 1968, 1969 and 1970.

As one of “the most influential and most widely read Black literary magazines” in the United States, the Negro Digest’s circulation peaked at 150,000 before its last issue in 1976.* Not only did the magazine feature up-and-coming African American writers, it was a place where intellectuals discussed the changes in Black America, focusing on Black empowerment and solidarity, while tackling the destructive tendencies of white supremacy.

My senior exercise is an exploration of the special editions from 1968-70. I look to the authors and articles within them as they explain their support for the concept of the Black University. I explore the Black University’s call for a Black education, run by Black faculty and staff, with a focus on curriculum that is not Eurocentric. I explore their criticisms of majority-white colleges that marginalize Black students. I look to the calls for a new curriculum that would raise the political consciousness of its students. They imagined an institution where students would go on to become political leaders in their communities. At the end of a powerful period of social activism, educators also took part in transformative discussions about how the United States should shift its worldview.

As you might be able to see, it’s not an easily encapsulated topic. There are so many strands to piece together in telling the story of the Black University. But telling its story is paramount to the entire experience of this research conference. The Black University asked for a deeper questioning of the methodology, tools and outcomes of higher education. In many ways, my presentation is a reflection of those questions. The exercise of presenting one’s research expresses the claims of the institution of higher education that I am enrolled in. In the history department, one of the explicit goals of this experience is to use the feedback from our audience to craft our final version of our research. The Black University also emphasized interaction with community, although in more political ways.

Sometimes I fear that my research doesn’t have the same impact of the radical claims of the Black University. My post here is a way to bridge that gap. I don’t want my research to be a hidden adventure. This is just one way to share the Black University’s vision.

As I look forward to the senior research conference, I feel butterflies in my stomach. I don’t think it’s a weakness to admit that I’m a bit nervous. Every historian feels a little unprepared in these situations. We ask ourselves, will I stumble through my presentation? Will there be questions I can’t answer? But I will try to take it as an opportunity to grow, and also a moment to appreciate that I am at the end of the road here. These are my last steps at Kenyon. I still have research to conduct and a final paper to compose, but this is the start of an end. Perhaps that is the part that makes me the most nervous.

The history department’s annual senior research conference will be held Sunday, Jan. 21 from 3-8 p.m. in Samuel Mather Hall.

*Margaret Alic, “Nathan Hare, 1934—: Sociologist, psychologist, political activist,” in Contemporary Black Biography, edited by Paula Kepos and Derek Jacques (Detroit, MI: Gale Cengage Learning, 2008), 83. Shari Dorantes Hatch, ed., "Negro Digest (1942-1951, 1961-1970); renamed Black World (1970-1976), and later First World (1977-1983)" in Encyclopedia of African-American Writing, 2nd ed (Amenia, NY: Grey House Publishing, 2009).